Beyond Compromise

How Value Polarization Hurts Democracy

The recent U.S. election cycle could not have made it more clear how polarized politics is in America today, and increasingly, in the West as a whole. Throughout the long campaign cycle, each side invariably refused to admit that the opposing side’s arguments or concerns were worth a solitary farthing. Journalistic interlopers at partisan campaign rallies attempting to engage on the battleground of ideas resulted in comedy at best, and severely depressing realizations about the desolate chasm spreading between the two sides, at worst.

Political punditry devolved completely into the silliness of “look at what celebrities we have on our side!” The moment Taylor Swift endorsed Harris, MSNBC (purportedly a news organization) lit up with the unmitigated delight of schoolchildren under a Christmas tree. This was concurrent with an abject reproach by the right, for example with Megyn Kelly childishly threatening that “you can kiss your sales to the Republican audience goodbye, Taylor!” (even as billions of fans continued to pay untold sums to grab tickets for her sold-out tour). All this from someone simply correcting a false narrative online that she was going to vote for Trump and encouraging others to do their own research and vote.

Political aisle-crossers like Tulsi Gabbard and Robert Kennedy were immediately rebuked by the citizens of the shore they departed, and welcomed with open arms by the other side like heroic pioneers on a new frontier, even though they had been summarily dismissed by them up until that point.

Trump supporters were adamant that if indeed their side didn’t end up winning, it could only have meant that the other side somehow stole it by cheating. Harris supporters bristled at the all but unavoidable prospect of violence if and when the Dems won the race, spending untold time and resources bracing for that possibility. The screeches of opposing pundits were deafening, touting the existential danger and dire consequences of casting the wrong ballot. America and the world prepared for “all hell breaking loose” in the days following election day.

In the end, the definitive Trump win left half of the country aghast and the other half awash in gleeful exuberance, and everyone scratching their heads about the uneventfulness of the concessions and promises for a peaceful transition. The claims about the prospect of cheating just didn’t seem to materialize on either side this time around, thank goodness, which I suppose is a testament to the relative normalcy on the Democratic side when compared with Trump’s Republicans’ reaction to 2020. From the outside, it seemed as though both sides were surprised at the extent of the win, with Trump taking all the battleground states and gaining ground in almost every demographic across the nation relative to his other two runs. The triumphant cheers and dancing in the online streets mingled with the wails and screams of the hair-on-fire losing team, making me wonder if I had accidentally gone trick-or-treating a few days too early this year.

The inevitable blame game for the Democratic party and media machine began its ramp, torches alight in a twisted and grotesque[1] witch hunt throughout the party and across all media outlets, on occasion lashing out at the voters themselves for their apparent short-sightedness. Given the level of confidence in the reasons provided for the overwhelming loss, it’s ironic that the losing side and their political and media machine didn’t just… do things differently beforehand. The day after the election, Jon Stewart deftly pointed out the absurdity of that kind of confidence.

Jon Stewart pointing to the absurdity of political prognostications - youtube.com

A mirror image of this would of course also have happened if the result were reversed, possibly with violence attached if January 6, 2021 is any representative measure, especially with Trump and Musk ginning up the stakes with false conspiracy theories for the last 3 months.

The final months of media coverage leading up to election day were exhausting. There was no hiding from the froth of untold billions spent in flooding the airwaves with political advertisements. The ratio of signal to noise felt like we were stumbling home at night in blistering snowstorm, armed only with a pocket flashlight. Irrespective of your politics, one thing was clear from this result: the tribal, political divide in the nation leading the free world had reached a fever pitch, a trend we also see developing in other Western nations as well, including Canada, where I live.

Throughout the cycle, the left would espouse value A, while the right would parry with the virtue of conflicting value B. And vice versa, both sides attempting to devour one another, finishing the meal with a liberal sprinkling of claims that the other side were fascists.

But hang on — is it any wonder that one can always find a pair of opposing values on any given issue?

The dearth of engagement with the position of the “other side,” and lack of any real attempt to integrate its values through debate, compromise, or at the very least by acknowledgement, was a major frustration for me, and I suspect many others. Why do they do this? Because divisiveness gets attention and clicks. It also allows you to substitute an unpopular narrative for a popular one by turning a group of people who all agree on issue 1 (“we should have a child tax credit”) against themselves on issue 2 (“immigrants are taking your jobs and ruining our cities”).

To all the screeching pundits: values are not interesting in and of themselves. Arguing over the cost or benefit of thing “A” without recognizing the benefit or cost of opposing thing “B” is simply not useful. Optimizing the dimension along which these opposing things apply tension requires that you give voice to both. Your value system informs which end of the spectrum you lean toward, i.e. which thing you value more, and why. Screaming “Value A!” from your soapbox and megaphone and chastising those who dare disagree does nothing to advance the discourse, assuming that’s what you’re trying to do.

Who would argue against the prospect of “freedom,” “autonomy,” “low taxes,” “better jobs,” and “cheaper milk”? It’s only when those values encounter one another where things become interesting, like when a woman’s right to control her own body contends with a developing child’s right to life, or when a trans woman’s right to define their own identity butts up against the right of women to compete in sports on a level playing field. Honest engagement on these topics would mean the candidate would espouse either the former or the latter on balance after weighing the costs and benefits of both.

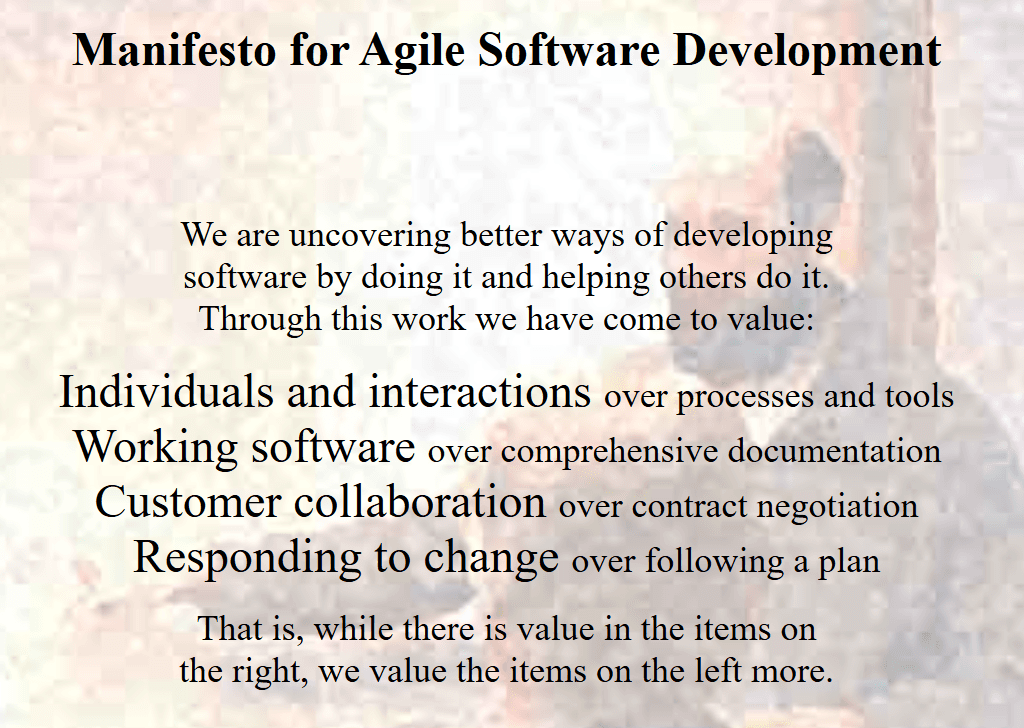

In the world of software development where I work, there is an analogue of this from which politicians and the media could learn:

Signatories of the manifesto concede that all eight of the listed aspects of software development have value, but they advocate for the “more important” subset of four. This provides a much better context for understanding the optimization. If this were a political debate, this approach would also allow opposing sides to better work across the aisle after the “election” was over, which in this metaphor would come down to a choice between an agile or waterfall method of delivery, or some compromise between the two.

Last week I watched stories of the left-leaning (and hilarious) Daily Show making fun of Trump’s rising cabinet hopefuls (Musk and Kennedy among them) as the “division of the X-Men for the mutants who had too much mutation” while at the same time hearing Jordan Peterson also use an X-Men analogy, except this time to extol the virtues of Trump’s transition team. The players and the analogy are the same, with completely different implicit conclusions, which says more about the commentators than the candidates themselves. If you’d only seen one of these, you might have walked away with a completely different conclusion than if you’d seen the other, or both.

The left points to the outlandish conspiracies, falsehoods, and sycophantic nature of Trump’s X-Men’s provocative public statements, whereas the right celebrates the X-Men’s intelligence, individual capability, and resistance to the creep of identity politics and woke-ism. There is truth in both sides, but falsehood in similar measure by each having omitted acknowledgement of the opposing side.

Daily Show X-Men Joke - youtube.com

Jordan Peterson X-Men analogy - youtube.com

Discourse 101 teaches us to first repeat back to your counterpart what you believe their point is. Doing this builds your credibility as a fair and thoughtful person who’s not simply trying to annihilate you with their opinions. This can be followed up with perspective, explaining why you believe it makes more sense to lean one way or the other, the totality of which creates your plank.

To his credit, in the treatise linked above Peterson’s briefly makes a light reference to Trump’s narcissism as a potential problem, but then prematurely papers over it by saying something to the effect of “what else can we expect of someone who wants to be president?”, negating the fact that the sheer mass of Trump’s narcissism could produce a black hole.

Peterson is obviously intelligent, and his psychological analysis of Trump’s X-Men is both revealing and entertaining, but fewer people will ingest and mull over his message owing to what he left out. Suppose that instead (as an example; I’m not saying that he believes this) he said something more like “Trump’s narcissism might be dangerous in the domain of foreign policy because opponents could play to his narcissism in exchange for political favour, but I believe this risk can be mitigated by his closest confidants, who would naturally protect against the need for such an exchange.” That would feel like the beginning of a conversation worth having.

In Elon Musk’s pre-election interview with Joe Rogan, there were many strategic omissions of opposing view acknowledgement, substantially reducing his credibility as well. He asserted that the Democrats “can’t claim to be the good guys if [they’re] deliberately pushing hoaxes that have been debunked thoroughly.” Ok, but your deafening silence on the sheer tonnage of hoaxes and lies pushed by Trump and his delegates speaks volumes. Additionally, Musk’s unhinged claim that the Democrats were flying immigrants into Pennsylvania to steal the election for Harris without any real proof or acknowledgement of how the other side might respond to that accusation further betrays his blind partisanship. And as it happens, this particular conspiracy never materialized.

The electorate would be much more likely to vote for any candidate approaching the discussion more honestly, even if they happened to lean in the opposite direction on parts of their platform. My best example of this in America in recent years is Bernie Sanders, who has been consistent and honest for decades, beating the drum on what he believes will make the difference for people — a $15/hr minimum wage and Medicare for all among them — all the while refusing to participate in the useless noise and mudslinging. He’s also shown an ability to make the compromises he needed to make to move his agenda forward throughout numerous presidential terms. Even if you disagree with his values or proposals, it’s obvious to see that he’s a fair and honest player on the field of ideas.

Thankfully, there were some examples of fair and honest rhetoric in this cycle as well, such as Tulsi Gabbard’s summer interview with Chris Williamson on the Modern Wisdom podcast. In one instance, she lays out the tension between the value of allowing the citizenry to make their own choices about what they read and say on digital platforms vs. the competing value of safety and security provided by government regulation of disinformation and mental programming on these platforms.

Chris tees up the tension more explicitly when he talks about the many pitfalls of TikTok in this context, and whether or not the platform should be banned. Tulsi clearly states her optimization between these competing values: “I choose freedom.” She then explains why she leans toward free speech as the more important value, owing to its ability to resist the creep of authoritarianism.

Tulsi Gabbard on safety vs freedom - MW podcast on youtube.com

When pushed on the addictiveness of TikTok and how it might even be a foreign government’s attempt to program America’s youth, she mentions “The Social Dilemma” documentary, conceding that it is a good source for arguments for protection, and suggests a bipartisan effort to bring more safety to kids while minimizing constraints on free access to information. She finally warns that governments will always be motivated to limit access to information that might remove them from power, and promote information that might keep them in power, which we saw with the Twitter files. In other words, she believes free speech, enshrined in the 1st amendment, to be the more foundational value.

Later in the interview, she also enjoins people to read the project 2025 doctrine for themselves and to “be a critical thinker” while remaining suspicious of the Democratic side’s weaponizing rhetoric around the document. Of course it would have been better if she’d read it herself, but at least she admits this and refuses to take a position on it.[2]

The comments section on the MW podcast episode feels like a breath of fresh air, with people repeatedly saying exactly that and more, in an overwhelmingly positive response to the tenor of the interview, “Tulsi for president, 2028” being a common refrain. Politicians take note: people crave thoughtful spaces that respectfully integrate and discuss opposing values, as opposed to rhetoric designed to massage one team’s existing opinions, identities, and in-group memberships.

Funnily enough, Gabbard’s discussion with Rogan makes it obvious that absolute concepts of “good” and “bad” are hard to come by in political discourse. A policy position just comes down to what you value more as an individual. Furthermore, recognizing that “different people value things differently than I do” might allow us to accept political losses more gracefully, understanding that a well-functioning democracy depends on this acceptance (and on the differences to create the tension promoting debate in the first place).

A discussion of value within the field of commerce is much less emotionally charged than a political one. We don’t bat an eye when two contractors quote differently for the same job. Similarly, two different clients may be willing to pay different amounts for the same job, with one perhaps valuing quality and workmanship and the other optimizing for speed and cost. It’s also why every share available on a stock market has multiple concurrent Bid and Ask prices, arranged in a ladder called the “level II market data,” clearly demonstrating a wide field of concurrent prices (values) for the exact same share.

Even more obviously, disparate value systems are why the sale of any product or service is even possible at all: the buyer believes that what she’s buying is worth more than the agreed price, and the seller believes that what he’s selling is worth less than the agreed price. Otherwise, no purchases would ever occur. This also implicitly happens whenever an employee is hired and a salary is agreed upon. And values can change over time. The phrase “that’s not worth it” implicitly means “that’s not worth it to me, right now.” Admonishing someone for having a different set of values seems absurd in this context.

A well-functioning democracy should be seen as a values optimization problem as opposed to a fight to the death. It all feels like Eddy Izzard’s “Death Star Canteen” bit, in which the canteen worker disarms Darth Vader’s battle stance by simply offering a tray, because “The food is hot!”

"Death Star Canteen" skit - Eddie Izzard on youtube.com. Classic.

We are tired of the divisive rancor on display by our media pundits and politicians. Our way forward might be to qualify candidates by first judging their honesty, by seeking out those who have some idea of how they purport to improve things for people and can communicate it, and by those who show they can recognize opposing values and views before explaining their policy choices.

Here are a few quick hacks to help you determine whether or not a politician is honest about their intentions:

You feel both calm and hopeful after you hear them speak.

They are sometimes openly critical of their own party or government — either locally or on the world stage — when they don’t agree with them, showing that they are willing to risk their position and power to promote their values. Check the voting record.

Their policy positions are relatively static over long periods of time, changing them only when the conditions have substantially changed, or they communicate good reasons for changing themselves. [3]

They often attract the ire of those in the political elite that can’t control them.

They invite you to do your own research rather than taking their word for it or shaming all those who to dare to dissent.

They are comfortable, forthcoming, and cogent in a long form interview format, in which their remarks are less easily scripted.

When you find someone like this, introduce them to those in your circle, and thereafter, hold their feet to the fire if they ever waver.

Of course, we must also look inward for solutions. Besides walking the talk and striving to be the honest actors we hope our politicians will be, there are several changes we can put into practice ourselves:

Continuously expose yourself to opposing viewpoints, debating them on a regular basis, as painful as this may be. Our own echo chambers blind us to fuller understanding and hide the optimal solutions we seek, ensnaring us as unwilling participants in the dogged realm of polarization.

Be respectful of opposing views, asking more questions, especially at the outset of any interaction, as opposed to simply defaulting to parry and riposte.

Be open to changing your mind if presented with better arguments or evidence. It can actually be fun when this happens if you have the right mindset, because you can feel yourself growing in real time!

Test opinions by asking “why do you believe that?” and search for reliable sources of those beliefs. Sometimes people don’t even realize that the origins of their own opinions are empty propaganda or untested groupthink, and can be steered in a better direction just by asking questions. Or they may do the steering by providing good answers.

Understand that you may not have full information, even if it feels like you do (it usually does). There are vested interests everywhere who are trying to get you to think one way or another. Instead of making prognostications, assign probabilities to the veracity of your own opinions, and update those with each new conversation.

I’m going to let Rogan and Gabbard wrap this article for me with this clip (1:13:40–1:16:27) (watch the whole discussion if you can) from her Summer 2024 segment on Joe Rogan.

Tulsi Gabbard on values - Joe Rogan podcast - youtube.com

Rogan: “You know, it’s just one of those things where, as it’s all playing out, there’s a sense of hopelessness because there’s not like a clearly defined path where this country’s ship gets righted. It’s like, I just see a lot of chaos and a lot of confusion and lot of infighting, and I don’t know how this plays out. It doesn’t seem like there’s a real clear ‘Oh, this is our path to sanity.’”

Gabbard: “You’re right. And I think the first step towards that path, though, is people recognizing what the insanity is, and the problems. And I think that more and more these things are coming to light. I can tell you … I mean, I know there are a lot of Democrats that feel the same kind of frustration that I feel with the Democratic Party Leadership

Rogan: “Often quietly; I mean there’s a lot of quiet disagreement where people are like ‘I’m not voting for Trump, but what the fuck are we doing?”

Gabbard: “Yes, right… and I think there’s that in the Republican Party as well. And so I think that that creates opportunity for us as a country to get out of just this two party system mindset, and this mindset of fear that drives so many of the elections, where instead of saying like ‘hey, I’m running for president because this is how I’m offering to lead the country, this is how I’m offering to serve the country. Here are the things that I’ll do.’ Instead of that we are kind of relegated to ‘hey, vote for me or vote for my party because the other guys is the devil.’ And, really treating voters like we’re idiots, and we don’t care or have the intelligence to actually look at ‘ok here’s where you stand on this issue, here’s where this other person stands on this issue. I’m going to make my decision not based on party but actually based on hey who best reflects my values? Who is actually going to put the country first… the interest of the American people and the country first?’ And not just the people who say the words but the people who have the record and the policy to back that up. And so, I hope that this is the direction we’re moving in as more and more people get disillusioned with leaders in both parties who care more about their own political ambitions and their own party’s power than they actually do care about the American people.”

[1] Lyric by Neil Peart, “Witch Hunt” — 1981

[2] Trump also disavows all knowledge of the document, but this is much harder to believe since he was running for president, and it’s clearly very much a part of his running mate’s agenda.

[3] Harris embraced Medicare for all when she thought it was a winner in 2020, only to ditch it when she believed it was politically expedient to do so. Trump always takes both sides of an issue and just discards one of the sides depending on what conversation he happens to be in.

Music from #Uppbeat (free for Creators!):

https://uppbeat.io/t/ak/night-drive

License code: DW3HWB1PXNAQAEKX

Here is a NotebookLM-generated AI reaction to this article, with audio-mixed backing music. It’s posted here mainly for those who prefer to listen in a podcast format than read a long-form article. The original article with audio read-through can also be found on the Summersoul website.

Music from #Uppbeat (free for Creators!):

https://uppbeat.io/t/ak/night-drive

License code: DW3HWB1PXNAQAEKX